A Question of Perspective

I’m a star junkie. Not the stars you see in the movies or read about in tabloids, as in “movie star,” but the kind you see when you look up at the night sky. White dwarfs and red giants – who would have thought that outer space would be inhabited by dwarves and giants?

I’m fascinated by them, by their shapes and sizes, by their names. Names like Betelgeuse, Alderbaran, Sirius, names heavy with history, dense with myth, names as thick and viscous as honey.

It wasn’t always this way. For a long time I had no interest in them.

My father is an astronomer. When I was growing up he was in school for a long time. I was seven the year he got his Ph D. He went through university on the GI bill and made extra money working summers for an electronics company. I think he assembled transistors for TVs in the days before microchips. The company he worked for is still in business — I saw its name in big, bold letters in the yellow pages last year when I was trying to get the thermostat on my kiln fixed.

For twenty years he worked at a university teaching and doing research. He was a professor at a medium-sized university in a medium-sized city. A couple of years ago he retired.

I’ve never been in the building where his office and lab were located, although I’ve seen it from a distance. It’s a plain cylindrical concrete structure, devoid of decoration, that stands ten stories tall in the middle of a flat field. It isn’t connected to any other building and its smooth surface is broken only here and there by rectangular windows that seem to have been added randomly as an afterthought. The building is self-contained and inscrutable.

At the top of the building is a telescope, housed in a room with a convex roof. When the telescope is in use, the roof retracts to reveal the sky. I know it’s often cold in there; the atmosphere in the room is kept the same temperature as the atmosphere outside the building so heat waves won’t rise off the surrounding material and distort what the telescope is observing. I also know you sit in a little cage to view through the telescope and that computers, not people, do most of the viewing these days.

I pick up this information in different places, on TV mostly, not from my father. He never talked about his work. When we were young and asked him about it, he’d make some dismissive remark and change the subject. I got the impression he felt we wouldn’t be able to understand what he was talking about.

My boyfriend Ron likes TV shows with a scientific bent. He’ll sit on the couch in the living room for hours watching documentaries about animals, ocean currents, climate change. He knows more about the sex life of whales than he does about our sex life I sometimes think. Me, I phase out after half an hour. I can muster only so much interest in the dietary habits of raptors, and if I have to watch one more show about any kind of insect I am going to invest in a big can of bug spray, no matter how toxic it is for the environment. But it was, obliquely, Ron and his TV tastes that got me hooked on stars, so I give him credit.

When I was a kid stars were never those tidy, five-pointed shapes you cut out of yellow construction paper to put on top of the pine tree in the living room at Christmas. That sort of ignorance was a luxury my father was not willing to indulge. He set us straight about stars and planets as fast as he could.

I remember a night when I was about eight years old. We had moved again. It seemed we moved all the time. In retrospect, my parents were probably constantly in search of a cheap apartment large enough to house two adults and three growing children, but I didn’t know that at the time. I only knew I kept leaving friends behind.

One night my father took mom, me and my two sisters up onto the roof of our new apartment building. When we stepped out into the night my eyes were flooded by darkness and for a moment I was blind. A chilly autumn breeze made me shiver and underfoot, pebbles embedded in the tar of the roof made walking barefoot uncomfortable.

It was the first time I had ever been up so high at night and as my eyes adjusted I was surprised at the number of lights below us. Streetlights glowed, car lights scooted along streets, across the street the gas station’s big illuminated sign threw a glaze of green light onto the faces of people walking past.

It seemed odd to me that all these lights made the night seem darker, not lighter. Their brilliance made the surrounding sky black, but when I looked directly above me, away from the lights, the sky was deep blue, not black; it seemed to move towards me and away at the same time.

Above me I saw stars that were no colour I could name, a sound instead of a colour — high-pitched, at the upper level of human hearing. Their flickering reminded me of still water disturbed by winds or by deeper currents of moving water.

My father stood beside us, one hand on my shoulder. He was pointing at the sky, naming names. “There’s Polaris, the North Star,” he said. “That group of stars is the Pleiades. Venus over there isn’t a star, it’s a planet. There’s the Big Dipper.”

My eyes follow his hand as it sweeps through the air but I can’t tell which stars he is talking about, there are so many and they seem so randomly placed.

He keeps talking and pointing. He tells us the distance from the earth to the sun is 93,000,000 miles, the distance from our sun to the closest star — a number too big to mean anything to me — from our galaxy to the nearest galaxy, until my head spins. He tells us how hot the stars are, how cold the empty reaches of space between them. He talks in millions and billions.

I can’t imagine a million, and even if I could, what would it matter? A mile is far to me; it takes a boringly long time to walk from our new apartment to the library a mile away. Multiply that by a million? Stretch that boredom from here to Sirius? It’s impossible for me to imagine. I am cold now, here, wearing my olive-green sweater with the wool worn into little balls at the wrists and waist — how to imagine the frigid expanse of outer space?

Still he talks, trying to explain things that feel too big for my head. Whatever he’s talking about is obliterated by the masses of stars up there, distant, haphazard, unconnected. The numbers he rattles off spin, make me feel dizzy.

“Look,” he says suddenly, jabbing at the sky. I do. I feel as though I’m falling into a wide, dark, bottomless pool.

After this, staring at stars gave me vertigo. I preferred to be earthbound. I cultivated common sense and was pleased to overhear someone say about me, “She’s so down to earth.” I’d had enough of speculation and abstraction. I wanted my world to be concrete. When my father rattled off numbers and theories at dinner I tuned out. I’d squirm in my chair and poke patterns into the soft pine dining room table with the tines of my fork until my mother glanced over and told me to stop.

In high school I gravitated to subjects that had clear right and wrong answers: math, accounting. The tactile pleased and reassured me.

After high school I went to art school where I would sit in the cafeteria and draw charts in my sketchbook of the course my life would take. I broke the process down into steps and numbered each step. Then I drew small circles around the numbers and leaned back in my chair, satisfied with the direction my life was taking.

Eventually I became a potter. I hoisted bags of silica, kaolin, and cobalt around. I wedged clay, set it on the wheel and formed it into pots. I lifted trays of pitchers, mugs and plates in and out of the kiln. I developed muscles, grew solid. I avoided abstraction and became an empiricist; what I could touch, I trusted. If I did look skyward it was to gauge the weather; firing a kiln on a humid day yields different results than firing on a dry day does.

I enjoyed the feeling of my strength and the idea that, just as I could shape pots from clay, I could fashion my life as I saw fit.

I learned facts. A potter needs to know facts. The relative hardness of certain substances, for example, and the melting points of different materials. To my mind, facts were small firm nuggets of reality to build my world with. I held them tight, they served as ballast to stabilize me. I liked tables, charts and graphs, information laid out neatly in visual blocks, specific information, limited and organized.

For the same reasons I like facts, charts and graphs, I liked Ron. He sold computers, a nice, straightforward job. He seemed anchored and steady. His choice of TV programs recommended him immediately. We did not go to bars or movies as many couples do when they are first getting acquainted; we watched Jacques Cousteau specials on TV and went to museums. Ron liked paleontology, but even that field was too hypothetical for my taste — too much theorizing and guessing involved, too many gaps that needed filling, not enough verifiable information to fill them. I preferred geology. The rocks were there, layer on layer, palpable and material, no guessing required. Iron is iron, it is never granite. No gaps, either, otherwise the Grand Canyon would tumble into the Colorado.

Ron and I lived together for three years before we bought our house, a small, two-storey, wood-frame farmhouse not far from where my father lived. It needed serious work. We found it at the end of a winter, took possession in spring, dismantled it through the summer, and partially reconstructed it during the fall. By the time the next winter rolled around most of the largest cracks had been sealed, but not, as we discovered when the cold east wind blew, all of them.

My studio was a small sunroom off the kitchen. It wasn’t insulated and although it caught the morning sun, when winter came and the winds buffeted against its walls the room was cold. I glued half-inch Styrofoam to the walls and moved in a small electric heater, but my efforts amounted to almost nothing. Cold seeped in through a bank of windows in one wall and around an outside door in the other.

I began to wear a sweater to work in there but I was still cold. I tried a windbreaker, but that didn’t do the job, either. Finally I bought a parka to wear. Wrapped in my olive drab coat with fake fur trim on the hood, I’d run hot water into my throwing bowl and waddle out to the studio. During the winter I took a break every hour, went into the kitchen to have a cup of coffee and thaw myself out.

The cold caused problems with the clay. Cold, it was stiff and difficult to manipulate. If I worked too long my hands became numb from the chill and grew clumsy, so that I ruined perfectly good pieces. The parka cut down on my mobility and on top of it all, our electricity bills were staggering. I struggled on anyway. People had worked through worse, I told myself, and I was not going to be defeated by a mere drop in temperature.

One night in mid-October Ron appeared in the doorway. “There’s a show on about astronomy,” he said.

“That’s nice.” I was concentrating on a lump of clay spinning in front of me.

I’ve already finished most of my Christmas stock. I made it during summer, now it is packed in boxes that can be stowed in my VW Rabbit. From this point until the end of December I’ll drive from one drafty community centre to another to hawk my wares. I’ll set up my booth, smile at passersby, subsist largely on stale donuts and rot gut coffee standard at these affairs and — I hope — earn sixty percent of my annual income.

But this year my large decorative platters with slip-trailed paintings of fish in the middle have turned out to be a hit. I’ve already sold most of them, so tonight I’m making more, but it’s not going well. There are times like this, occasionally, when I’m out of rhythm with the clay, or the clay is uncooperative. It doesn’t centre on the wheel, the forms wobble off-balance, or if they pull out, they do it too quickly and the walls are uneven and fragile.

Eventually I manage to pull out a platter, but the edges crumble and fray into ribbons in my hands. Finally I shut off the wheel, shuck off my coat and shoes, and head into the kitchen, closing the door behind me. I cross to the sink, wash the clay off my hands and gouge it out from under my fingernails. Then I wander into the living room.

The lights are off and the TV is on as I come through the doorway into the room. Ron’s horizontal on the couch; I can’t see his face. All I see is the TV screen vivid with motion. Liquid light flows from the screen, glazing the walls and floor. The surfaces that face the TV are brilliant, all the rest dissolve into gradations of grey and black. Only where light meets matter are objects in the room actual, all else fades into intangibility.

A man’s voice, rich and plausible, rolls out of the TV. On screen a shot of the sun fades into blackness then, pinprick by pinprick, dots of light appear on the screen: stars in the night sky. “The building blocks of the universe,” the voice intones.

The voice rolls on, explaining, discussing, weighing. Images jostle on screen but I am intent on an inner picture: I see a great fountain spilling stars and planets into the black void of the unformed universe. In my imagination the fountain is made of many tiers which diminish in size as the fountain ascends. Stars and planets fly out from the top of it in a spume of foam, and tumble away through pathless space.

Ron looks up. “How’d it go?”

I shrug off the question and we talk about other things.

A year earlier my mother had died. She had been sick for years so her death shouldn’t have been a surprise, but it was. My father especially seemed stunned by it, which was unexpected since he had cared for her through her decline so he, more than the rest of us, knew how ill she was.

Before this I had interpreted his reserve as preoccupation. He was thinking about abstruse matters, uninterested in unimportant details of day-to-day life. Now it seemed as if he thought of one thing constantly, something close at hand, heavy and wearing, that he worried at the way a dog worries at a wound.

The summer after my mother’s death he went on vacation by himself. When he returned he handed me a box. “Here,” he said.

I opened the box and found, nestled in the tissue paper, rocks, pebbles, really, the sort of thing I might find if I stepped out the back door and scrabbled in the dirt. “To match the rocks in my head?” I asked jokingly.

“I picked them up at the bottom of the Grand Canyon,” he said. “I thought you might like them.”

“Thanks,” I said. Rocks, I thought. Great. Wondering if there was a secret meaning to the pebbles in my hand.

What with the craft shows, I didn’t have much time to buy Christmas presents. A couple of days before Christmas I was in a bookstore looking for something on recombinant DNA — a little light reading for Ron — when I found myself in the astronomy section poring over books. I found one that came with a make-your-own constellation kit, star shapes cut out of phosphorescent paper that had adhesive backing, and a map of the night sky to help lay out the constellations.

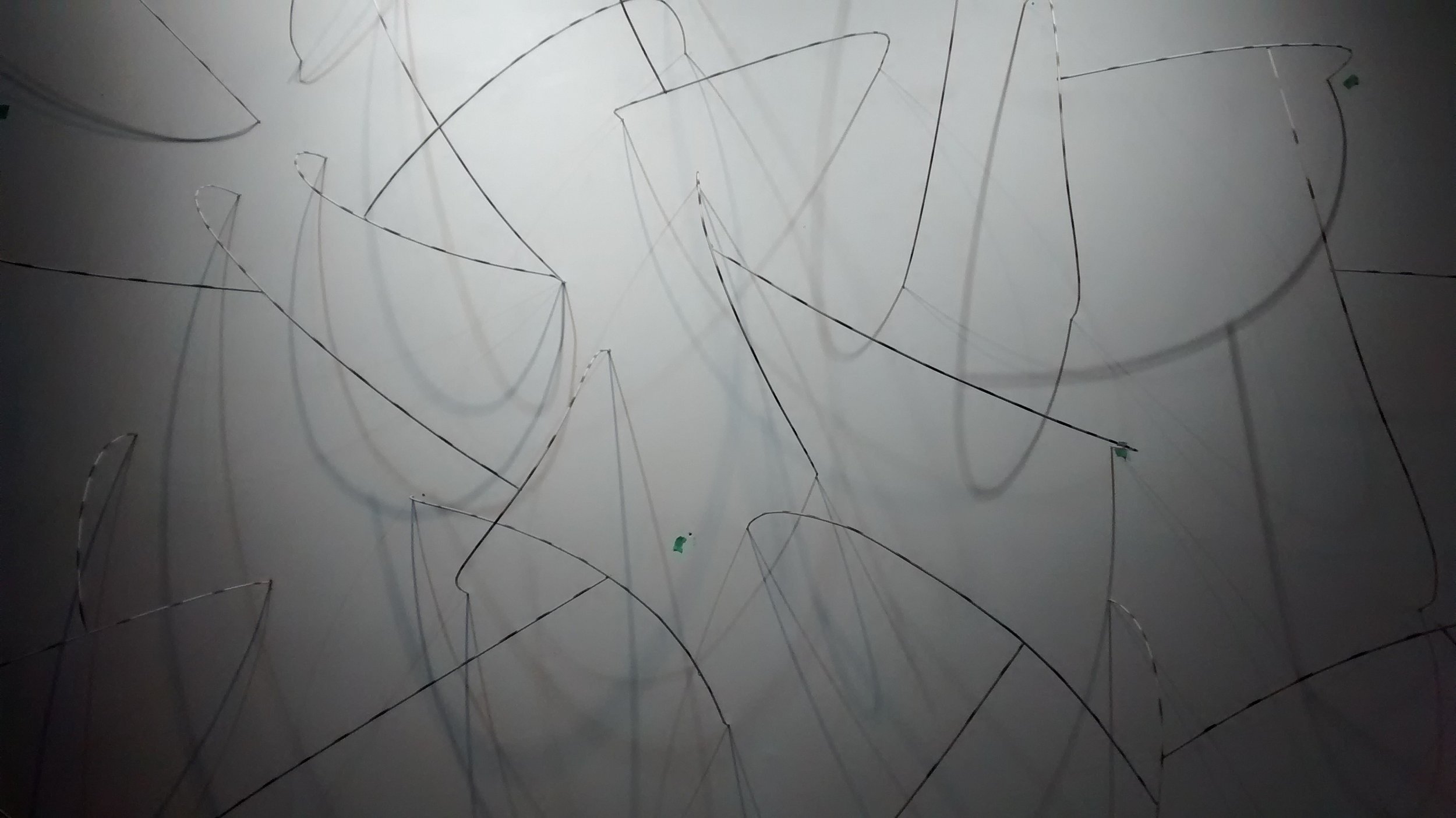

I bought the book and left the store. When Ron came home from work that evening he found me in my studio, balanced on a chair, a star in my outstretched hand as I tried to decide exactly where to stick it.

“Maddie?” He sounded tentative.

I unsquinted my eyes to focus on him. “What’s up?” he asked, glancing around the room at the detritus of starts, star maps, coffee cups.

“I’m working on Cassiopeia.”

He glanced at the wall. “Oh,” he said. “Well, good.” He paused as if he was waiting for me to say more. When I didn’t, he continued, “I’ll call you when dinner’s ready.”

The next week I bought a telescope and set it up in our bedroom on the second floor. When he sees it, Ron says, “In our bedroom?”

“It’s the best place.”

“What is all this anyway?” he asks. “Constellations on the walls and ceilings, now a telescope. Why?”

I shrugged. “I just thought it was interesting.”

My Christmas sales are good. I decide I can take about a month off before I have to start getting ready for the summer craft shows.

One afternoon I’m in the kitchen making pastry — the oven is on, the air is warm — when I hear a knock at the front door. I walk down the hall, wiping flour off my hands with a red and white dishtowel.

I open the door and for a split-second find myself facing a white-haired stranger. The moment passes; I recognize my father.

“Oh,” I say. “Hi.”

“I was in the neighbourhood,” he says.

“Come on in. Want a cup of coffee?”

He follows me down the hall, sits at the kitchen table and takes the coffee I set in front of him. “I’m just rolling out a crust.” He nods and leans back. Quiet settles.

“What’s this on the wall?” he asks.

“Constellations.”

“So I see,” he says. “A hobby of Ron’s?”

“No, I put them up.”

“Oh.” He pauses. “I didn’t know you were interested in that kind of thing.”

“I didn’t know until recently myself.” I stop fiddling with the pastry and turn around, leaning against the counter. “It’s interesting, all that stuff. The Big Bang — one minute nothing, the next, everything; entropy — the idea everything just gets more and more chaotic — ”

“I’m not sure that’s strictly what entropy’s about,” he says.

“Well, anyway,” I say, sitting across the table from him. “There are things I find it hard to wrap my head around, the randomness of things, and the enormity. It makes stuff — people’s lives — seem negligible.” Although I don’t phrase it that way I realize I am asking him a question.

My father sits looking at the stars on the wall for a while. After a few minutes he says carefully, “I don’t accept that. I don’t believe life is negligible.” He pauses. “It’s a question of perspective.”

I begin to ask him what he means by this but Ron comes home in a burst of noise and activity. The two of them settle into conversation about DNA. I go back to making dinner.

Later that night, after dinner, after the dishes have been washed, I put on my clay-encrusted parka and go outside. I walk to the top of the small hill that rises behind the house. It’s late winter, there’s still snow on the ground but the earth feels yielding underfoot, as if some of the groundfrost is already seeping away. In the air is the flat, clean smell of winter but below that runs a dark undertone that hints at mud, rain, and seeds blindly sending out white shoots into the black, moist soil.

Standing on the hill I consider what my father said: a question of perspective. Perspective, I think, depends on where you stand and it determines your relation to what you’re looking at.

I remember how I had opened the door earlier to find a stranger on the porch. For an instant I’d thought, “Who’s this?” but before I had even finished framing the thought, recognition, like a camera focusing, made his face familiar. Of course, I said to myself, Dad.

Still — there was that tremor of uncertainty when he was still a stranger, when what I saw were white hair, a lined face, an old man.

In art school, before I made the decision to immerse myself in clay, I took a course in architectural rendering. We did perspective drawings; a flat horizon with a vanishing point, scratchy lines radiating from it, these are what I remember.

But it occurs to me now that perspective is more than simply a technique for charting the gradations of distance and diminishment.

Above me are the stars. I know they are huge balls of burning gas, eons away from where I stand. The light from them is pale and watery, but it’s enough to see by. However randomly and intangibly, I am linked to those distant stars by that light. This is perspective, too, then — understanding the net of connections that binds and sustains us. Impalpable as time, it is somehow satisfying. A good place to begin.

Melanie Dugan

1991